The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent | Est. 2002

"Spam Private Eye" Can't Constitutionally Be Required to Get Real Private Eye License,

at least when the license requires 6000 hours of training on matters far removed from his expertise.

From Fink v. Kirchmeyer, decided last week by Judge Rita Lin (N.D. Cal.):

Joel Fink operates a business called "Spam Private Eye" where he reviews his clients' "junk" emails and identifies ones that might violate California's anti-spam law [and can thus support lawsuits seeking statutory damages -EV]. In July 2023, the California Bureau of Security and Investigative Securities (the "Bureau") cited Fink for acting as an unlicensed private investigator.

The court concluded that the regulation was "a content- and viewpoint-neutral regulation of professional conduct" and thus "subject to rational basis review, requiring only a showing that the licensing requirements are rationally related to Fink's fitness to conduct his business." But, though "[t]hat is a low bar," "the private investigator licensure law fails to clear that low bar as applied to [Fink]":

Specifically, he has shown a gross mismatch between the highly burdensome requirements of the licensing regime, which require him to undertake 6,000 hours of largely unrelated training, and the State's marginal interest in regulating his review of his clients' "junk" emails, which are highly unlikely to be sensitive.

As a result, the court issued a preliminary injunction against the Bureau's applying the law to Fink, reasoning:

#TheyLied Libel Lawsuit Over Ex-Student's Allegations of Rape Can Go Forward,

and so can the professor's Title VII and Title IX discrimination claims against the university.

From Erikson v. Xavier Univ., decided Monday by Judge Matthew McFarland (S.D. Ohio):

Erikson was a tenured Associate Professor of Art for Defendant Xavier University for nearly a decade until his termination in October 2022. This case primarily revolves around the events leading up to Plaintiff's termination; a former student's [Witt's] allegation that Plaintiff had raped her and the investigative and administrative actions that Xavier took in response to her formal complaint.

Plaintiff began speaking with … Witt[] during the latter half of 2019. Although Witt had graduated from Xavier in 2013, she was not a Xavier employee and had no other relationship with Xavier. After communicating over several months and meeting on multiple social occasions, Witt suggested that she spend the night at Plaintiff's house on December 31, 2019. That night, Witt visited Plaintiff at his house and the two had sex. Plaintiff alleges that the sex was consensual.

A little over two years later, on February 5, 2022, Witt contacted Defendant Kelly Phelps—a professor at Xavier who chaired the Department of Art from 2012 through 2019. Witt told Phelps that she believed Plaintiff had raped her. Phelps "urged Witt to report the allegation but warned her that [Plaintiff] is 'white, and male, [and] got privilege on his side."

On February 24, 2022, Plaintiff was notified that Witt had filed a formal complaint with Xavier alleging that Plaintiff had violated Xavier's policy by raping her on December 31, 2019. Plaintiff "vehemently denied" the accusation. Additionally, Plaintiff informed Xavier that any investigation into Witt's formal complaint would breach the terms of Xavier's Harassment Code and Accountability Procedures ("HCAP") for several reasons: "(1) at the time of the incident, Witt was not a student or an employee, nor did she have any other relationship with Xavier; (2) the alleged incident did not occur on Xavier property or during an event associated with the University; (3) Witt was not a 'visitor' to Xavier at the time of the alleged incident; and (4) in any event, the alleged incident occurred outside the HCAP's two-year statute of limitations for filing complaints."

Xavier held an HCAP hearing regarding the rape allegations on July 22, 2022 and July 25, 2022. During the hearing, "the panel embarked on a moral tirade against [Plaintiff] for, as a male, having sexual intercourse without using a condom." The panel allowed witnesses to make vague references to allegations of Plaintiff's conduct beyond the scope of Witt's complaint and permitted hearsay testimony by witnesses without personal knowledge. Moreover, the panel ignored testimony that Witt had consented to the sexual activity. The panel ultimately found Plaintiff responsible for raping Witt and recommended terminating him from Xavier. The panel attributed the rape to an "imbalance of power" between Plaintiff and Witt, which stemmed from the fact that Plaintiff is a male whose position in life and at the University seemingly granted him status and power. This power allowed Plaintiff to overwhelm Witt's ability to resist his actions. Xavier terminated Plaintiff in October 2022.

$160K Libel Verdict for Ex-Student Based on Professor's Research Misconduct Allegations

In Rossi v. Dudek (D. Utah), plaintiff sued her former professor for libel, based on his allegations that she had committed research misconduct. Such allegations of misconduct that are made within an employer or an educational institution are often "conditionally privileged," which means (to oversimplify) that liability is only allowed when there's a showing of (1) knowing or reckless falsehood, (2) a motivation of personal hostility, or (3) communication to people who don't have a professional reason to know about the controversy. Last week, the jury rendered a $160K verdict in Rossi's favor, and Monday Judge Ted Stewart refused to set aside the verdict, holding that the jury could find that the conditional privilege didn't apply:

Dr. Jeffrey Botkin, the Vice President for Research Integrity at the University of Utah during the time Plaintiff was a student, testified that it was his job to determine if enough evidence had been produced to open an investigation into potential research misconduct. Dr. Botkin testified that Defendant could not articulate a sufficient rationale for his concerns, that his concerns lacked specificity, and he did not provide specific evidence to support his allegations of research misconduct. Accordingly, Dr. Botkin concluded there was not sufficient evidence to initiate an investigation at that time.

Dr. Botkin testified that he communicated that information to Defendant. Defendant then testified that, following this determination by Dr. Botkin and Dr. Botkin's reminder to keep concerns confidential, he [presumably Defendant -EV] continued to express his concerns about research misconduct with committee members, people in his lab, and family members.

Defendant also testified that accusations of research misconduct are serious and highly damaging to a scientist's reputation. Other witnesses … Defendant testified he did not like Plaintiff, did not trust her, and did not want to work with her. Defendant testified that Plaintiff's comments regarding his lack of availability to her caused him to believe she falsified her data, but there has been testimony from several witnesses … that Defendant failed to follow up to verify the truthfulness of his accusations and failed to produce specific evidence of his accusations. Defendant testified that he never tried to verify if his accusations of research [presumably meaning "research misconduct" -EV] were false, despite his access to all the data stored on Plaintiff's laboratory computer within Defendant's laboratory.

Defendant further testified that, even after Dr. Botkin's instruction to keep concerns about research misconduct confidential, he continued to share his concerns with people beyond the Research Integrity Office and the thesis committee. Defendant testified that he shared his research misconduct accusations with his daughter Amanda while she was a student at Harvard University, Dr. Kevin Staley at Harvard University, and other members of his lab, who did not have a legitimate role in resolving the dispute….

Based upon this evidence, the Court finds that Plaintiff has presented sufficient evidence such that a reasonable jury could find that any applicable privileges have been abused by common law malice, actual malice, and/or excessive publication.

The court also concluded, for similar reasons, that defendant couldn't claim governmental immunity.

Ryan B. Hancey and Adam Lee Grundvig (Kesler & Rust) represent plaintiff.

Harlan Institute-Ashbrook Virtual Supreme Court Finalists

The top 8 teams presented oral argument in Moody v. NetChoice.

The topic for the 12th Annual Harlan Institute–Ashbrook Virtual Supreme Court competition is Moody v. Netchoice. We have now held the Round of 8 and the Round of 4. The teams were superb. Truly, these high school students could compete in any law school moot court competition. The championship round will be held next month in Washington, D.C.

Round of 4

Round of 4 Match #1: Team #17038 v. Team #16886

Round of 4 Match #2: Team #17485 v. Team #17050

Round of 8

Brief Opposing Pseudonymity in Ohio Libel Case

I thought I'd pass along this friend-of-the-court brief that I just filed a couple of days ago in the Ohio Court of Appeals (Doe v. Roe), with the help of invaluable local counsel Jeffrey M. Nye (Stagnaro, Saba & Patterson) and UCLA LL.M. student Bhavyata Kapoor.

[* * *]

This is a garden variety defamation lawsuit of the sort that is routinely litigated in the parties' own names. Many defamation litigants would prefer to avoid being linked with the accusations over which they are suing—just as many plaintiffs and even more defendants would prefer to avoid being linked with the allegations in many kinds of cases, allegations that may reflect badly on one or both parties. But our legal system has chosen to adopt a strong norm of public access to court records, including to the names of the parties, so that the public and the press can better supervise how the legal system operates. And this is not one of the rare cases in which an exception from this norm is warranted. The trial court thus did not abuse its discretion in ultimately deciding to deny pseudonymity. See Doe v. Cedarville Univ., 2024-Ohio-100, ¶ 18, __ N.E.3d __ (2d Dist.) ("[A] trial court's ruling regarding a party's request to proceed pseudonymously will not be overturned absent an abuse of discretion.") (cleaned up)….

[I.] There is a strong presumption against pseudonymous litigation

Today in Supreme Court History: March 21, 1989

3/21/1989: Texas v. Johnson is argued.

Progressive Lawyers Engage In Actual Judge Shopping In Alabama

"Surreptitious Steps" to draw a Carter appointee in a deep red state demonstrate why the Judicial Conference's policy would not work.

From what I've gathered, the Judicial Conference's ill-fated policy is all-but-dead. What a blunder it was. Rather than focusing on areas of bipartisan agreement like patent and bankruptcy reform, the judges leaned into a contentious, hot-button issue. I worry that the well has now been poisoned for broad reform, though I'll share some thoughts in due course about how to improve things.

For now, I'd like to highlight some actual judge shopping in Alabama. And none of this judge shopping occurred in single-judge divisions. You see, Alabama has very few Democratic-appointed district court judges. By my rough count, in the entire state, there is one active Obama nominee, and two senior appointees from Clinton and Carter. The Carter appointee, Judge Myron Thompson in Montgomery (Middle District of Alabama), is well known for ruling in favor of progressive litigants. Unsurprisingly, if you are a progressive litigant in Alabama, you will do everything in your power to get the case assigned to Judge Thompson.

Which brings us to the present case. In 2022, Alabama enacted the Vulnerable Child Compassion and Protection Act, which prohibits certain medical procedures for minors. As could be expected, the law was subject to immediate challenges by all the usual suspects.

Their strategy, which was revealed in a panel report, is striking. Here is the (rough) chronology.

- 4/8/2022—Ladinsky complaint filed in NDAL by National Center for Lesbian Rights, GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders, Southern Poverty Law Center, and Human Rights Campaign.

- 4/11/2022—The NDAL case was randomly assigned to Judge Annemarie Axon (Trump appointee).

- 4/11/2022—Walker complaint filed in MDAL by ACLU, Lambda Legal, and Transgender Law Center. The civil cover sheet marked the case as related to Corbitt v. Taylor. Corbitt was a challenge to an Alabama policy regarding the listing of gender on drivers' licenses. That case had been closed in January 2021. The only lingering issue was attorney's fees. Judge Thompson presided over Corbitt. The attorneys "marked Walker related to Corbitt because they wanted Walker assigned to Judge Thompson." The attorneys admitted that "they considered Judge Thompson a favorable draw because of his handling of Corbitt and that he ruled in favor of the plaintiffs who asserted transgender rights claims."

- 4/12/2022 – Walker randomly assigned to Chief Judge Emily Marks (Trump appointee). Walker plaintiffs filed a motion to reassign to Judge Thompson. Counsel had also called Judge Thompson's chambers and spoke with the judge's law clerk to flag the pending motion for preliminary injunction. At that time, Walker had not been assigned to Judge Thompson. (The lawyer at first denied making such a call, but later admitted it; the panel found his testimony was "troubling.") The counsel never called Chief Judge Marks to flag the pending motion.

- 4/13/2022—Chief Judge Marks entered an order to show cause why the case should not be transferred to the Northern District. The parties did not oppose the transfer.

- 4/15/2022 – Walker reassigned to NDAL, and the case was randomly assigned to Judge Burke (a Trump appointee). That day, Judge Axon also transferred Ladinsky to Judge Burke. About two hours after Ladinsky was assigned to Judge Burke, the Walker and Ladinsky plaintiffs filed a notice of voluntary dismissal. This dismissal was made, "even though (as [counsel] admit) time was of the essence and their stated goal was to move quickly to enjoin what they viewed as an unconstitutional law, abruptly stopping their pursuit of emergency relief."

- 4/16/2022—Counsel for Ladinksy plaintiffs tell the press that they plan to refile their case "immediately."

- 4/18/2022—Judge Burke denied the TRO as moot because of voluntary dismissal, but noted the press reports that the Plaintiffs planned to refile. Judge Burke stated, "At the risk of stating the obvious, [p]laintiffs' course of conduct could give the appearance of judge shopping—'a particularly pernicious form of forum shopping'—a practice that has the propensity to create the appearance of impropriety in the judicial system."

- 4/19/2022—A new group of plaintiffs, led by Eknes-Tucker, filed suit in the Middle District of Alabama signed by the same lawyers who filed Ladinsky. The lawyers found new plaintiffs, because were "concerned that they would be accused of judge shopping if they filed a new action with the same plaintiffs." The case was randomly assigned not to Judge Thompson, but to Judge Huffaker (Trump appointee).

- 4/20/2022—Judge Huffaker transferred the case to Judge Burke.

The panel concluded, "Behind the scenes, counsel took surreptitious steps calculated to steer Walker to Judge Thompson even before filing their motion to have Walker reassigned to him." And the lawyers "made plans and took steps in an attempt to manipulate the assignment of these cases." Ironically, the panel noted, Judge Burke ruled for the Eknes-Tucker plaintiffs in part. A Trump judge!

This sequence of events, which was well known in Alabama, proves how pernicious actual judge shopping is. And this practice has nothing to do with single-judge divisions. Skilled lawyers know how to direct cases to favorable forums. Here, they made some ill-advised statements to the press, and got caught. But in many other cases, they are not caught. I will wait to see breathless outrage on social media about this actual judge shopping. If ADF did something like this, they would be crucified.

How would the much-vaunted Judicial Conference have worked here? Who knows!? There were so many assignments and reassignments, coupled with suits filed in competing divisions, all based on random draws. These choices were deliberately made by the plaintiffs to gum up the system. Plus, the coversheet and "Related Case" gambit throws a wrench in any assignment wheel. Often, staff in the clerk's office have to decide whether to reassign a "related" case. This case involved "two cases [that were] filed in the same district and there [was] a question about whether they should be consolidated or otherwise transferred so that the same judge presides over them." Resolving this issue is "not so much a rule as a practice." It is complex, and requires some judging. It would not surprise me if judges in the trenches looked at the Judicial Conference's policy and recognized that it would be impossible to actually apply in the real world–especially in light of potential gamesmanship. After all, parties can trigger reassignment just by seeking statewide relief. Or, a case could be dismissed and re-filed, as the plaintiffs did here. Or the same complaint can be filed in multiple districts, with the hopes of getting the best draw.

The attorneys in the Alabama case work at leading law firms and civil rights organizations. They have every interest in avoiding random draws in red states. For these reasons, I suspect they would quietly oppose the judicial conference's policy.

The RBG Leadership Awards are Rescinded

A few days I go, I blogged about the rather insensitive action by the Dwight Opperman Foundation to award the RBG Leadership Awards this year to a bizarre list of honorees: Elon Musk, Rupert Murdoch, Martha Stewart, Michael Milken, and Sylvester Stallone.

On Tuesday, then Foundation backtracked and cancelled this year's award ceremony "after facing blistering criticism from her family and friends over this year's planned recipients," in the words of the NY Times.

A good move; if I'm going to chastise them for screwing up, I should applaud when they recognize their mistake and try to put things right.

No Sanctions in Michael Cohen Hallucinated Citations Matter

From today's decision in U.S. v. Cohen by Judge Jesse Furman (S.D.N.Y.) (see also N.Y. Times [Benjamin Weiser]):

In support of his motion [for early termination of supervised release], Schwartz [Cohen's lawyer] cited and described three "examples" of decisions granting early termination of supervised release that were allegedly affirmed by the Second Circuit. See id. at 2-3 (citing United States v. Figueroa-Florez, 64 F.4th 223 (2d Cir. 2022); United States v. Ortiz (No. 21-3391), 2022 WL 4424741 (2d Cir. Oct. 11, 2022); and United States v. Amato, 2022 WL 1669877 (2d Cir. May 10, 2022)). There was only one problem: The cases do not exist. Although the Government failed to point that fact out in its opposition to Cohen's motion, E. Danya Perry—who entered a notice of appearance on Cohen's behalf following the Government's submission—disclosed in a reply that she had been "unable to verify" the citations in Schwartz's filing….

Schwartz (aided by his own counsel) and Cohen (aided by Perry)[,] … [w]ith one exception discussed below, … tell the same basic story. In early November 2023, Schwartz sent a draft of what would become the November 29, 2023 motion to Cohen. Cohen asked Perry (who had not yet entered an appearance in this case) to provide feedback on the draft, which she did. One comment, which Cohen passed along to Schwartz, was that the motion should cite a few cases granting early termination. Schwartz adopted what he understood to be Perry's suggestions and sent subsequent drafts back to Cohen.

On November 25, 2023, Cohen then sent three emails to Schwartz with the cases in question and summaries of the cases. Cohen had obtained the cases and summaries from Google Bard, which he "did not realize … was a generative text service that, like Chat-GPT, could show citations and descriptions that looked real but actually were not. Instead, [he had] understood it to be a super-charged search engine …." According to Cohen, he did not "have access to Westlaw or other standard resources for confirming the details of cases" and "trusted Mr. Schwartz and his team to vet [his] suggested additions before incorporating them" into what became the motion.

That trust proved unfounded.

Justice Barrett's concurrence in McCraw will increase the number of emergency appeals on the Shadow Docket

The Shadow Docket giveth, The Shadow Docket taketh away

Justice Barrett's concurrence in McCraw made it less likely that lower courts will grant administrative stays before a merits panel holds oral argument. And, it turns out, the administrative stays from the Fifth Circuit were not coming from the Court's trumpiest judges. Before the ink even dried on the Supreme Court's shadow docket order, the Fifth Circuit panel (Richman, Oldham, Ramirez) swooped into action. First, on Tuesday afternoon, the panel set oral argument for Wednesday morning (it is ongoing as I type). This oral argument is only on the question of whether a stay should be granted pending appeal. A merit-stage oral argument is set for April 3. Second, the panel dissolved the temporary administrative stay over Judge Oldham's dissent. I suspect the writing is on the wall, and this panel will not grant a stay pending appeal. It is possible the en banc court can override this decision. Chief Judge Richman, according to my 2022 count, is far from the median voter on the Fifth Circuit. But the Fifth Circuit may let this one linger for regular en banc review.

Going forward, I'm not sure if Justice Barrett's concurrence will have the effect that she intended. Let's spin out two scenarios. First, where a district court judge in Austin rules against Texas. Second, where a district court judge in Amarillo rules against the federal government. In both scenarios, if Justice Barrett's approach is followed, the courts are less likely to enter administrative stays for any lengthy duration. And, the average Fifth Circuit panel would probably grant a stay in the case from Austin, and deny the stay in the case from Amarillo. What is the effect? More emergency applications arriving at the Supreme Court filed by the Department of Justice. Yes, in an attempt to tighten the screws on the shadow docket, Justice Barrett likely made the shadow docket even more active.

What will the result be? Ironically enough, Circuit Justice Alito will be forced to enter a never-ending series of administrative stays that are extended as needed to digest complicated cases, which is what happened in McCraw. The Justices will be in the same position as the Fifth Circuit judges who are struggling to handle the torrent of emergency litigation. The shadow docket giveth, and the shadow docket taketh away.

Interesting Speech or Debate Clause Issue in Devin Nunes' Libel Lawsuit Against NBC

From yesterday's opinion by Magistrate Judge Sarah Netburn (S.D.N.Y.) in Nunes v. NBCUniversal Media, LLC:

The discovery issues before the Court may present questions of first impression. Because the parties did not adequately address these matters, the Court requests additional briefing.

Specifically, the Court seeks supplemental briefing on who is the holder of the constitutional Speech or Debate privilege asserted by counsel for the House Permanent Selection Committee on Intelligence ("HPSCI"). Assuming that the privilege is held only by a Member of Congress, and not a legislative committee, does a Member waive the privilege when he initiates a civil lawsuit about matters protected by the privilege? Alternatively, if the filing of a lawsuit does not constitute a wholesale waiver of the matter at issue, may a Member selectively waive the privilege as to certain relevant matters but not others? …

On March 18, 2021, when Devin G. Nunes, the Plaintiff, was a Member of Congress, NBCU, through a telecast of The Rachel Maddow Show, published a single allegedly defamatory statement: "[Devin Nunes] has refused to hand [the Derkach package] over to the F.B.I." "The Derkach package" refers to a package sent by Andriy Derkach, reportedly a Russian agent who attempted to influence the 2020 U.S. presidential election. According to Nunes, he "did not accept a package from Derkach." Rather, Nunes claims that the "package came to the House Intelligence Committee," and he "immediately turned the package over to the F.B.I."

Do Judges Also "Berate" The Press?

On Monday, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Murthy v. Missouri. Justices Kavanaugh and Kagan–who both worked in the White House–stated that it was fairly common for government officials to "berate" the press.

Justice Kavanaugh observed that "experienced government press people throughout the federal government . . .. regularly call up the media and berate them." Later, Justice Kavanuagh asked if "traditional, everyday communications would suddenly be deemed problematic"? Justice Kagan added that "like Justice Kavanaugh, I've had some experience encouraging press to suppress their own speech." Whereas Kavanaugh referred to "government press people," Kagan spoke in the first person about her own calls to the press. Kagan explained that "this happens literally thousands of times a day in the federal government." And she offered what such a phone call would sound like:

"You just wrote about editorial. Here are the five reasons you shouldn't write another one. You just wrote a story that's filled with factual errors. Here are the 10 reasons why you shouldn't do that again."

I can imagine being on the receiving end of such a phone phone call from Kagan or Kavanaugh. Indeed, some years ago, I received just such a call. I tweeted about an opinion from a federal circuit judge. The next day, I received an email from the judge asking me to call chambers. I promptly did so. At that point, the circuit judge proceeded to berate me for what the judge perceived to be an inaccurate tweet about the opinion. I tried to explain tweets are very short messages, that can't always capture all the nuances of a complex opinion. My explanation did not suffice. I was told that I should know better, and should take care to accurately characterize the opinion. The phone call went on for some time.

This experience was the most extreme judicial berating I've received, but it is not isolated. Another time I attended a conference and bumped into a circuit judge. I had recently severely criticized a decision from the judge's court. I introduced myself, and the judge replied, with a look of scorn, "I know who you are." No further words were exchanged.

Sometimes, judges use intermediaries. In one instance, a judge complained to my former boss, Judge Boggs, about a blog post I wrote. Judge Boggs relayed the message to me, and I shrugged. Another judge complained to one of my co-authors about something I wrote; I shrugged. In other instances, I've received contact from a judge's former clerks who defended their boss against something I wrote. More shrugging.

I've had other run-ins with judges who gently criticized my writings, or at most, suggested that I got something wrong. Most of the time it is done with some humor and humility, but on occasion, I can tell I've peeved the judge. These experience reinforce a point I've made in recent posts: judges profoundly care what the public thinks about them, and when they feel treated unfairly, they speak out.

I don't think inferior judges are unique. Supreme Court Justices likewise berate the press. In recent memory, perhaps the most visible such incident was when Justice Scalia wrote a letter to the editor of the National Law Journal, calling an article by Tony Mauro "mauronic." And in the Dick Cheney duckhunt case, Justice Scalia charged that many press outlets did "not even have the facts right" and gave "largely inaccurate and uninformed opinions." Scalia, perhaps to his credit, was open with his criticism. Other Justices make these remarks in private.

I am reliably informed that the Justices will often call members of the Supreme Court press corps into chambers for a discussion about their reporting. Of course, the very people who are best equipped to talk about these beratings are unable to do so. But if I had to guess, while Justices Kagan and Kavanaugh were asking their questions during Murthy, the fourth estate in the press box was nodding along.

Today in Supreme Court History: March 20, 1854

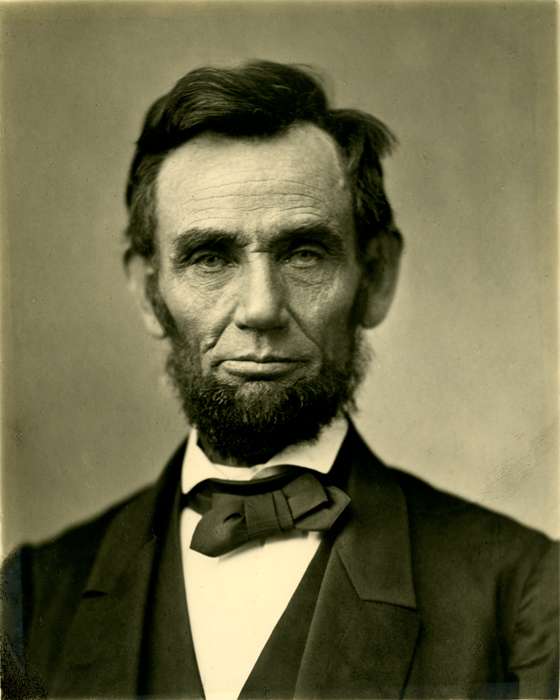

3/20/1854: The Republican Party is founded. President Abraham Lincoln would be elected President on the Republican ticket six years later on November 6, 1860.

Who is responsible for the 5th Circuit's alleged "troubling habit of leaving 'administrative' stays in place for weeks if not months"?

The worst offender is not Jim Ho, but Carl Stewart.

In the latest iteration of United States v. Texas, Justice Sotomayor observed that the "Fifth Circuit recently has developed a troubling habit of leaving 'administrative' stays in place for weeks if not months." She cited five cases. Those same five cases were cited in the Solicitor General's application to vacate the stay (at 15 n.3).

Would you care to guess which judges were on the panels that granted those administrative stays? Certainly is must be a super-Trumpy panel with Judges Ho, Duncan, and Wilson, right? Not exactly.

Here are the panels that granted the temporary administrative stays that Justice Sotomayor complained about:

- United States v. Abbott, No. 23–50632 (85 days, from Sept. 7, 2023, to Dec. 1, 2023) (Stewart, Graves, Oldham).

- Petteway v. Galveston Cty., No. 23–40582 (41 days, from Oct. 18, 2023, to Nov. 28, 2023) (Jones, Higginson, Ho).

- Missouri v. Biden, No. 23–30445 (66 days, from July 14, 2023, to Sept. 18, 2023) (Stewart, Graves, Oldham).

- R. J. Reynolds v. FDA, No. 23–60037 (57 days, from Jan. 25, 2023, to Mar. 23, 2023) (King, Jones, Smith).

- Campaign Legal Ctr. v. Scott, No. 22–50692 (48 days, from Aug. 12, 2022, to Sept. 29, 2022)(Higginbotham, Stewart, Dennis).

Of these fives cases, Judge Stewart, a Clinton appointee, voted to grant a stay in three of them. Judge Graves, an Obama appointee, voted to grant a stay in two of them. Judge Oldham, a Trump appointee had two. Judge Jones, a Reagan appointee had two. And Judges Ho, and Smith each had one.

After these temporary administrative stays were issued, the cases were accelerated to the next available oral argument session. And in Petteway v. Galveston County, in particular, Judges Jones, Higginson, and Ho set the temporary administrative stay to expire after 15 days.

What lesson do we draw here? Judges of all stripes on the Fifth Circuit grant temporary administrative stays. I think they are doing their best to handle this torrent of emergency motions, many of which are filed by the United States and progressive groups. It is hard to make a decision in short order with limited briefing. Don't forget–by the time a case gets to SCOTUS, there has been a full vetting below. But the circuit judge on emergency duty has a very full plate. The temporary administrative stay helps to get through the rush.

Justice Barrett raised some fair questions on how administrative stays should be granted. But neither the SG nor Justice Sotomayor have put forward any evidence that these temporary stays are being used in some sort of evasive fashion to evade the usual stay-pending-appeal standard. There is also a related point. If the District Courts in Texas are doing such crazy stuff, then the Fifth Circuit should be rewarded for granting these stays! But that sort of argument defeats the narrative.

There is no smoke here. And there is no fire. No shadows either. Justice Kagan was prudent to write her own dissent, and not join Justice Sotomayor's dissent.

The Sequel to Doe v. Mills: Justice Barrett Tightens The Screws On The Shadow Docket

The center of the Court wants to push back on temporary administrative stays and the Fifth Circuit.

Today, the Supreme Court issued an order on the emergency docket in United States v. Texas. To avoid confusion with the umpteen other cases by that name, we can call the case Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center v. McCraw. This case presented a challenge brought by the federal government against Texas S.B. 4. The District Court entered preliminary injunction to block the law from going into effect. On March 2, a three-judge panel of the Fifth Circuit entered a "temporary administrative stay." The panel also stayed that temporary stay for seven days to permit an appeal to the Supreme Court. The panel also expedited the case for the April argument session.

Two days later, on March 4, the Solicitor General sought an application to vacate the stay of the preliminary injunction. Circuit Justice Alito promptly administratively stayed the case until March 13. On March 12, the Court extended the administrative stay until Mach 18. And on March 18, the stay was "hereby extended pending further order of Justice Alito or of the Court." It was a stay on top of a stay on top of a stay on top of a stay. Stays all the way down.

Today, the Court denied the application to stay the Fifth Circuit's temporary administrative stay. In other words, the Supreme Court's stay was dissolved. As a result, the Fifth Circuit's temporary administrative stay will go into effect, and thus S.B. 4 can be enforced. As is often the case, there was no opinion of the Court. There was only a single sentence without any reasoning. However, there were separate writings.

Justice Barrett wrote a five-page concurrence, which was joined by Justice Kavanaugh. In many regards, Barrett's Las Americas v. McCraw concurrence is the sequel to Barrett's Doe v. Mills concurrence. In October 2021, Justice Barrett wrote her influential concurrence in John Does 1-3 v. Mills, which was joined by Justice Kavanaugh. This decision, in my view at least, heightened the standard required to obtain relief on the emergency docket. She wrote that the "likelihood of success on the merits" factor from Nken reflects "a discretionary judgment about whether the Court should grant review in the case." At the time, I wrote that Justice Barrett cut the fuse on the shadow docket, by making it harder to grant emergency relief. Over the past 2.5 years (yes it has been that long), Justice Barrett has consistently voted to grant emergency applications from the Biden administration and likeminded groups, often citing Doe v. Mills. More often than not, she lines up opposite of the Fifth Circuit.

Barrett's McCraw concurrence makes several primary points.

First, Barrett writes that if the Fifth Circuit had issued a stay pending appeal, the Supreme Court would have reviewed that decision with the four-factor test from Nken v. Holder. Here, Barrett cited her Doe v. Mills concurrence. But the Fifth Circuit panel did not actually issue a stay pending appeal. Rather, the panel only issued a temporary administrative stay until the case is argued before a merits panel. Barrett describes this posture as "very unusual." In dissent, Justice Kagan did not "think the Fifth Circuit's use of an administrative stay, rather than a stay pending appeal, should matter."

Second, Justice Barrett issues a deep dive into administrative stays, relying in large part on a recent article by Rachel Bayefsky in the Notre Dame Law Review. Barrett writes that administrative stays usually do not consider likelihood of success. Rather, quoting Bayefsky, administrative stays "freeze legal proceedings until the court can rule on a party's request for expedited relief." The administrative stay "buys the court time to deliberate" and decide whether the applicant is likely to succeed on the merits. Barrett cites a number of cases in which the Supreme Court issued a temporary administrative stay to "permit time for briefing and deliberation," including June Medical v. Gee, Murthy v. Missouri, Yeshiva University v. YU Pride, and McCraw itself. Barrett then cites a slew of circuit court decisions; some of which are cited in Bayefsky's article, but some are not. ACB did some original research.

Third, in a footnote, Justice Barrett observes that the Court has "not explained the source of a federal court's authority to enter an administrative stay." She cites Bayefsky for the proposition that this power comes from "a court's inherent authority to manage its docket, as well as to the All Writs Act, 28 U. S. C. §1651." I have not given this issue much thought, but I will.

Justice Jackson Seems to Be Charting a More Speech-Restriction-Tolerant Approach

Justice Jackson, like Justice Breyer (whom she replaced and for whom she clerked), seems to be considering an approach that is more embracing of speech restrictions that she views as especially urgent—including perhaps ones that departs from precedents such as the Pentagon Papers case.

In recent decades, the Court has been extremely skeptical when the government, acting as sovereign (as opposed to employer, subsidizer, educator, etc.) tries to suppress speech based on its content. But of course there has also long been a tradition of Justices arguing in favor of allowing restrictions when the government's needs appear especially urgent. Justice Breyer offers a recent example, and of course past Justices had taken similar views. Chief Justice Rehnquist was more embracing of speech restrictions, for instance, especially in his early years. Justice Frankfurter was another example, back in the 1940s and 1950s. (For more on the link between Justice Frankfurter's and Justice Breyer's approaches, see here.)

Yesterday's Murthy v. Missouri argument suggests that Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson may take a similar approach. Recall that the heart of the case is about two related but conceptually separate issues: (1) whether the government coerced platforms into restricting certain user speech; (2) whether, if the government merely substantially encouraged platforms to restrict such speech rather than coercing them, that would itself be subject to First Amendment scrutiny. Most of the Justices asked the lawyers about these two matters, and about related procedural questions.

But several of Justice Jackson's questions raised the possibility that the government may indeed be allowed even to coerce platforms into restricting speech—including speech that doesn't fall within the familiar First Amendment exceptions (such as for true threats or solicitation of crime). Some excerpts (emphases added):

[1.] I understood our First Amendment jurisprudence to require heightened scrutiny of government restrictions of speech but not necessarily a total prohibition when you're talking about a compelling interest of the government to ensure, for example, that the public has accurate information in the context of … a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic.

So … I'm just interested in the government sort of conceding that if there was coercion, then we automatically have a First Amendment violation….

[2.] [T]here may be circumstances in which the government could prohibit certain speech on the Internet or otherwise. I mean, … do you disagree that we would have to apply strict scrutiny and determine whether or not there is a compelling interest in how the government has tailored its regulation?

The First Amendment, the Fourth Amendment, and Substantial Encouragement

Part of the Murthy v. Missouri challengers' claim is that the First Amendment bans the government from even "substantially encouraging" private entities to block user speech. And as I noted in the post below, I appreciate the difficulties with this claim (though I also appreciate its appeal).

Here, though, I wanted to repeat one narrow observation that I had made some time ago. I'm not sure how far it goes, but it struck me as worth noting.

Consider this passage from the oral argument by the federal government lawyer:

I'm saying that when the government persuades a private party not to distribute or promote someone else's speech, that's not censorship; that's persuading a private party to do something that they're lawfully entitled to do, and there are lots of contexts where government officials can persuade private parties to do things that the officials couldn't do directly.

So, for example, you know, recently after the October 7th attacks in Israel, a number of public officials called on colleges and universities to do more about anti-Semitic hate speech on campus. I'm not sure and I doubt that the government could mandate those sorts of changes in enforcement or policy, but public officials can call for those changes.

The government can encourage parents to monitor their children's cell phone usage or Internet companies to watch out for child pornography on their platforms even if the Fourth Amendment would prevent the government from doing that directly.

All of those are contexts where the government can persuade a private party to do something that the private party's lawfully entitled to do, and we think that's what the government is doing when it's saying to these platforms, your platforms and your algorithms and the way that you're presenting information is causing harm and we think you should stop ….

A forceful position, I think; and yet note that, when it comes to many Fourth Amendment situations, the analysis may actually be quite different.

Show Comments (649)