Supreme Court Says Officials Who Block Critics on Social Media Might Be Violating the First Amendment

The justices established guidelines for determining whether that is true in any particular case.

When Donald Trump was president, he provoked a First Amendment lawsuit by banning critics from his Twitter account. "Once the President has chosen a platform and opened up its interactive space to millions of users and participants," the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit ruled in 2019, "he may not selectively exclude those whose views he disagrees with." Although that case became moot after Trump left office, the issues it raised have come up repeatedly across the country because public officials, regardless of their political party, are united in resenting criticism and often prefer to silence irksome constituents rather than simply ignoring them.

In two unanimous decisions published on Friday, the U.S. Supreme Court held that such blocking can violate the First Amendment and clarified the standard for determining when it does. The justices did not actually resolve either case, instead sending them back to the lower courts for reconsideration in light of its newly announced guidelines.

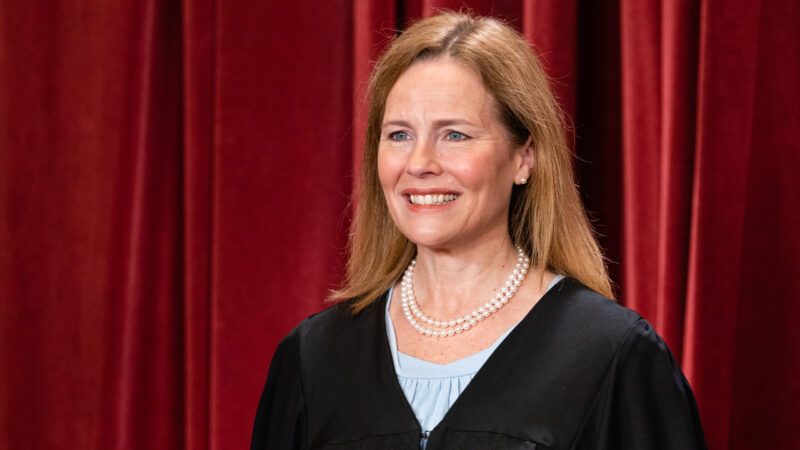

"When a government official posts about job-related topics on social media, it can be difficult to tell whether the speech is official or private," Justice Amy Coney Barrett writes in Lindke v. Freed. "We hold that such speech is attributable to the State only if the official (1) possessed actual authority to speak on the State's behalf, and (2) purported to exercise that authority when he spoke on social media."

That case involves Port Huron, Michigan, City Manager James Freed, who as a college student "created a private Facebook profile" that he initially "shared only with 'friends.'" He later made the page public and, after he was appointed city manager in 2014, updated it "to reflect the new job," using "a photo of himself in a suit with a city lapel pin" and noting his position in the "About" section. Freed "posted prolifically (and primarily) about his personal life," but he "also posted information related to his job."

The job-related topics included Freed's visits to local high schools, "reconstruction of the city's boat launch," "the city's efforts to streamline leaf pickup and stabilize water intake from a local river," and "communications from other city officials." Sometimes Freed "solicited feedback from the public," and he would delete comments he viewed as "derogatory" or "stupid." During the COVID-19 pandemic, he posted information on that subject, such as "case counts," "weekly hospitalization numbers," "a description of the city's hiring freeze" and "a screenshot of a press release about a relief package that he helped prepare."

Freed's discussion of the pandemic prompted Port Huron resident Kevin Lindke to vent his opinions about the city's "abysmal" response. "The city deserves better," Lindke wrote. After "Freed posted a photo of himself and the mayor picking up takeout

from a local restaurant," Lindke "complained that while 'residents [we]re suffering,' the city's leaders were eating at an expensive restaurant 'instead of out talking to the community.'" At first, "Freed deleted Lindke's comments." Eventually, Freed blocked Lindke, meaning "Lindke could see Freed's posts but could no longer comment on them."

That decision provoked Lindke to sue Freed under 42 USC 1983, arguing that Freed had violated his First Amendment rights under color of law. Lindke said Freed had "engaged in impermissible viewpoint discrimination by deleting unfavorable comments and blocking the people who made them."

That lawsuit is viable only if Freed was acting in his public capacity when he blocked Lindke. If Freed was acting as a private citizen, there would be no basis for arguing that he violated the First Amendment.

A federal judge rejected Lindke's claim, concluding that Freed's decision to block him did not qualify as "state action." The judge noted that Freed's posts were mainly personal, that the government was not involved with his account, and that Freed did not use it to conduct official business.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit upheld that ruling. Noting that "the caselaw is murky as to when a state official acts personally and when he acts officially," the appeals court asked "whether the official is 'performing an actual or apparent duty of his office,' or if he could not have behaved as he did 'without the authority of his office.'" In the social media context, the appeals court held, that means an official's activity amounts to state action if the "text of state law requires [him] to maintain a social-media account," he uses "state resources" or "government staff" to run the account, or the account "belong[s] to an office, rather than an individual officeholder."

Freed's activity, the 6th Circuit concluded, did not meet that test. But that test, Barrett says, does not account for the subtleties that courts must consider in cases involving public officials' use of social media.

"Lindke cannot hang his hat on Freed's status as a state employee," Barrett notes. "The distinction between private conduct and state action turns on substance, not labels: Private parties can act with the authority of the State, and state officials have private lives and their own constitutional rights. Categorizing conduct, therefore, can require a close look."

Since a Section 1983 claim requires that "the conduct allegedly causing the deprivation of a federal right be fairly attributable to the State," Barrett says, it makes sense to ask whether an official "possessed actual authority to speak on the State's behalf." Under that prong, she says, "a defendant like Freed must have actual authority rooted in written law or longstanding custom to speak for the State." That authority "must extend to speech of the sort that caused the alleged rights deprivation." And if "the plaintiff cannot make this threshold showing of authority, he cannot establish state action."

Because "state officials have a choice about the capacity in which they choose to speak," Barrett adds, an official "is speaking in his own voice" unless he is speaking "in furtherance of his official responsibilities." She illustrates the point with the example of a school board president who announces the lifting of pandemic-related school restrictions at a board meeting, then shares the same information "at a backyard barbecue with friends whose children attend public schools." The former announcement "is state action taken in his official capacity as school board president," she says, while "the latter is private action taken in his personal capacity as a friend and neighbor."

The situation with Freed's Facebook account is "hazier," Barrett writes, because he mixed clearly personal posts with job-related posts and did not include any explicit statement about the nature of the page. "Categorizing posts that appear on an ambiguous page like Freed's is a fact-specific undertaking in which the post's content and function are the most important considerations," she says. "Hard-to-classify cases require awareness that an official does not necessarily purport to exercise his authority simply by posting about a matter within it. He might post job-related information for any number of personal reasons, from a desire to raise public awareness to promoting his prospects for reelection. Moreover, many public officials possess a broad portfolio of governmental authority that includes routine interaction with the public, and it may not be easy to discern a boundary between their public and private lives. Yet these officials too have the right to speak about public affairs in their personal capacities."

Because of these fact-specific and context-dependent challenges, the Court vacated the 6th Circuit's decision and remanded the case "for further proceedings consistent with this opinion." It did the same thing in O'Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier, which involves two California school board members who blocked two parents of students on Facebook and Twitter.

Those decisions, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit ruled, constituted state action because there was a "close nexus" between the board members' "use of their social media pages" and "their official positions." But "because the approach that the Ninth Circuit applied is different from the one we have elaborated in Lindke," the Supreme Court said, the lower courts need to take another look.

Show Comments (23)